Home › Forums › Music Theory › …so, what exactly is a “key”?

- This topic has 7 replies, 5 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 9 months ago by

Jean-Michel G.

Jean-Michel G.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

October 30, 2023 at 10:29 am #353833

The concept of “key” is closely related to the transition from modal to tonal music in the Western Baroque period during the 17th century. The “Ionian mode” became the “major key” and the “Aeolian mode” with a raised 7th degree became the “(harmonic) minor key”. All the other modes were put aside.

It is as simple as that.Since there are twelve distinct notes in the Western chromatic scale (some of them having enharmonic names), and since each note can be the tonic of 2 keys (one major and one minor), you end up with 24 keys. At least, this is what is being taught in conservatories, academies and music colleges all over the world (when it comes to tonal music, of course).

In tonal music, A minor is a key in its own right, and not just the Aeolian mode of C major, because tonal music and modal music obey very different “rules”: you don’t play in A minor like you do in A Aeolian.

If you don’t consider A minor as a key:

– you cannot easily make sense of the major 7th interval and the V7 chord in the harmonic minor scale

– there is no room for the ii° chord and consequently there’s no ii° – V7 – i cadence that is pervasive in classical music (and in jazz!)Why did that transition happen?

Primarily for aesthetic reasons.

The Ionian mode (major scale) is the only mode (scale) in which there is a semitone between the 3rd and 4th scale degrees and another semitone between the 7th scale degree and the octave (tonic). This gives this particular scale more tension and release potential than any other mode.

In particular, it is the basis of the fundamental I – IV – I and I – IV – V – I cadences, the uber-important V7 – I resolution, and the melodic hierarchy of the notes in the scale.

A similar train of thought applies to the harmonic minor scale.

So these two scales allowed musicians to invent a musical vocabulary and make the most colourful music at that time.It is worth remembering that during the 300 years of what its usually called the Common Practice era, musicians didn’t use our equally tempered scale, but some sort of unequal temperament (there were plenty of them). So for them, a given chord did NOT sound the same in all keys! For example, the Dm in C major did not necessarily sound the same as the C#m chord in B major. That’s because in an unequal temperament the interval between chord tones of the respective chords are not exactly the same. The subtle but very real differences between keys was in fact also a major part of the musical language at that time.

So what?

The definition of a “key” is arbitrary in the sense that it depends on technical choices and cultural biases. And whenever something is arbitrary, other choices are indeed possible. But the problem, when you make other choices, is that you need to be consistent and rebuild parts of the theories that depend on your choices.

I definitely go with 24 keys because from my perspective, the “there are only 12 keys” point of view has many pitfalls down the road, despite the fact that it seems to offer an initial simplification.…but in the end, you see and decide for yourself.

-

October 30, 2023 at 11:44 am #353834

I see your point, J-M. I hadn’t considered the minor harmonic and melodic scales.

John -

October 30, 2023 at 2:28 pm #353835

Man, it sucked to live back in the 1700s. Nobody could spell properly, nobody knew what the notes of a scale were, and you had to work for some rich dude if you wanted to make a decent living as a musician and have the time to ponder such things. Not like today, where all guitars have 12 frets between the nut and the midpoint of the strings. Of course, the people in India never could agree on the proper position of the frets, so they just made the frets all adjustable on sitars.

Sunjamr Steve

-

October 30, 2023 at 9:10 pm #353848

Hi Jean-Michel:

Really interesting discussion, and very clear.

One point interested me especially. Can you comment on the different rules that govern tonal music vs. modal music, i.e., what are the differences in how you play in A minor vs. how you play in A Aeolian?

Thanks for sharing your know how!

Tom

-

October 31, 2023 at 11:04 am #353852

Interesting. It would never have occurred to me that it is a point of contention that Am, for example, is a key in its own right.

I mean, if I am at a jam, I will most definitely call out a tune as being in Am. And everyone understands that Am is the “home” chord and to expect to see some C’s, F’s, G’s and E7’s somewhere along the way.

-

November 1, 2023 at 5:25 am #353870

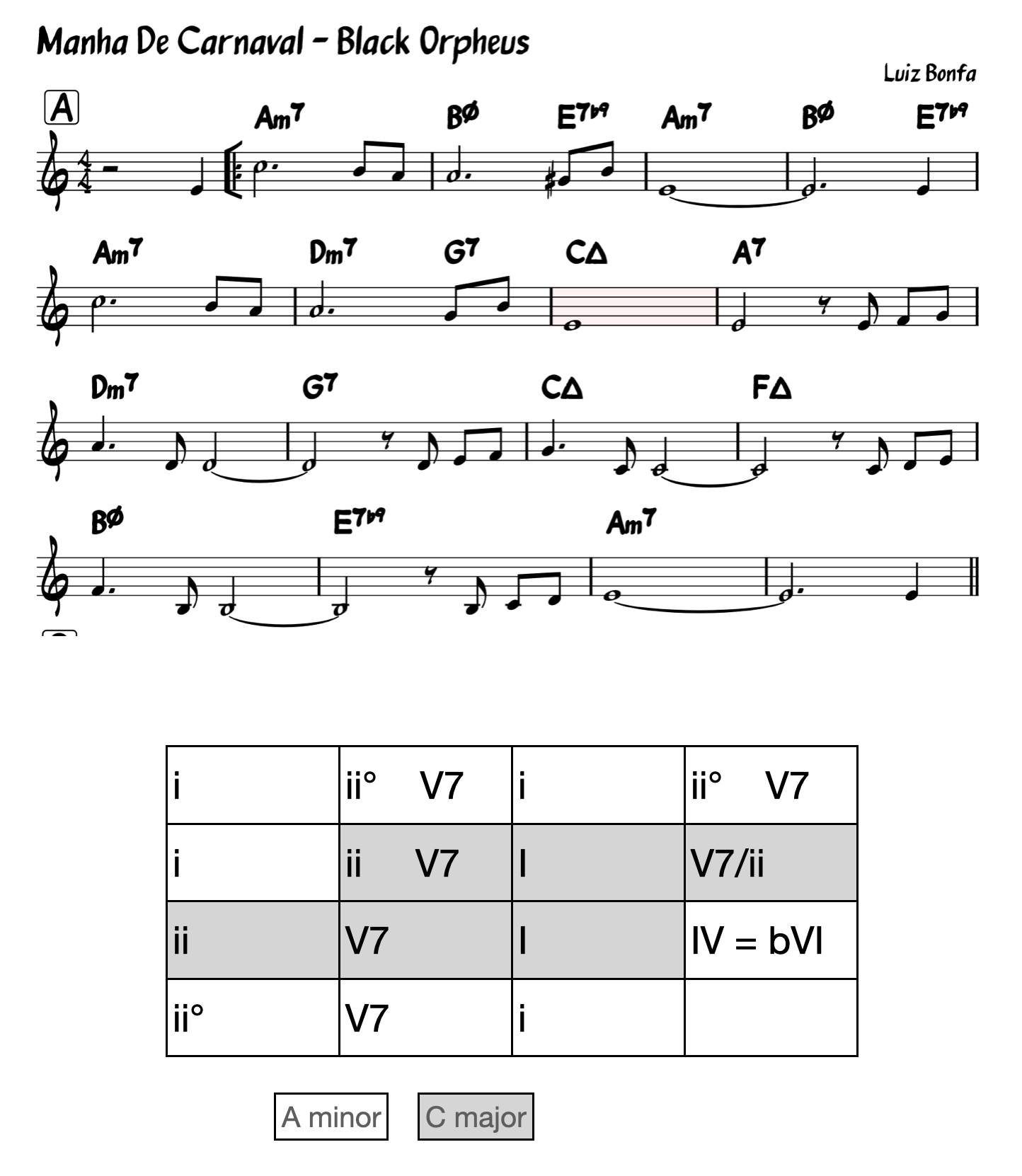

A comprehensive analysis of the differences between tonal music and modal music is way beyond the scope of a post like this one. So we’ll unfortunately just scratch the surface by looking at two examples. The tonal song that I’ll use as example is section A of the song “Manhã de Carnaval” by Luis Bonfa. It is a bossa nova song that first appeared in the movie “Orfeu Negro”. The modal example will be the well-known traditional “Scarborough Fair”.

1. Manhã de Carnaval

This song is definitely in A minor; it uses the natural and harmonic minor scales interchangeably but the dominant chord is always V and never v.

One thing that should be obvious when looking at the sheet, is the abundance of strong tonal cadences. There are V – I and II – V – I cadences all over the place.The harmony uses rich chords. This is partly due to the jazz nature of the song, but it can nevertheless be considered a characteristic of tonal music. J.S. Bach’s chorales use equally complex harmonies.

Also, there is a key change at bar 7, where the song modulates to C major, the relative major key of A minor. The song modulates back to A minor at bar 14. Key changes are relatively frequent in tonal music.

2. Scarborough Fair

Looking at the melody and the harmony, we seem to be in some sort of A minor context: the tonal center is very clearly A and the key signature is empty. But contrary to the previous example, there are no strong tonal cadences. The song ends on a Em – Am “cadence” which has the V – I chord root movement but is a much weaker conclusion than the corresponding E7 – Am cadence of the minor key due to the absence of tritone.

Also note that the harmony is generally much lighter as it uses mostly triads, and there are less chords.This is an example of a modal song that uses two parallel modes: A Aeolian and A Dorian (which is slightly brighter and happier). Note that you could also consider it to be entirely in A Dorian. I tend to “hear” two modal atmospheres, but it is rather subjective.

There are no harmonic functions in modal music: the chords don’t necessarily go anywhere, at least not nearly as strongly as in tonal music. In fact, you don’t want them to go anywhere. Modal music is harmonically much more peaceful and stable than tonal music. For that reason, the diminished triad and the half-diminished chord are not used in modal harmonies because they are too unstable.

Also, you’ll want to avoid any tonal cadences. For example, in A Aeolian, you would avoid a Dm – G – C sequence that would sound like a ii – V – I in C major.I hope this gives at least an idea of the differences between tonal and modal music.

Regards,

JM -

November 1, 2023 at 10:13 pm #353889

Wow J-M. Thanks for the thoughtful introduction for all of us. Your examples are GREAT and I’m looking forward to getting to know these topics. I very recently learned Eva Cassidy’s version of Autumn Leaves and am thinking it would be another good example to consider.🙏🏻 Tom

-

November 2, 2023 at 2:21 am #353890

Oh yes, “Autumn Leaves” is also purely tonal all the way through! It’s basically a constant balancing between a II – V – I in a major key and the II – V – I in the corresponding relative minor key.

-

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.